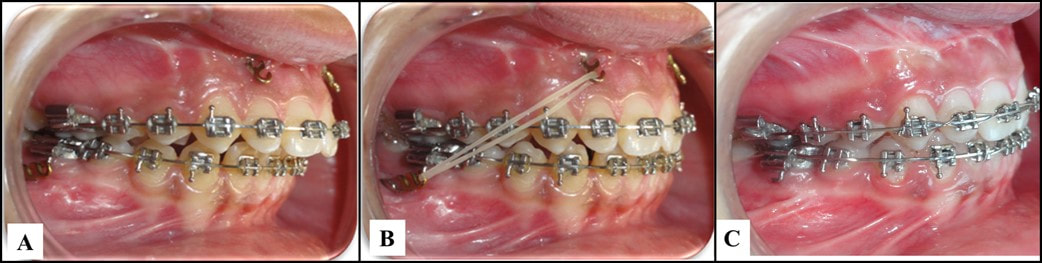

A, The miniplates after the healing period; B, application of the intermaxillary elastic; C, finishing to Class I molar and canine relationships. From Al-Dumini et al. 2018. A, The miniplates after the healing period; B, application of the intermaxillary elastic; C, finishing to Class I molar and canine relationships. From Al-Dumini et al. 2018. By TATE H. JACKSON and TUNG T. NGUYEN STUDY SYNOPSIS The use of skeletal anchorage for true orthopedic effect in growing Class III patients has now been well documented. Might the same strategy, using skeletal plates in both the maxilla and mandible, be effective to modify mandibular growth in Class II patients? A recent publication provides some initial evidence that it might. 28 growing children (age 11.83 +/- 0.83 years) with an ANB of 5 or greater, an OJ of 5mm or greater, and a ½ cusp Class II buccal relationship or greater were all treated with a standardized protocol by a single orthodontist. Each patient first went through alignment with fixed appliances for an average of 7 months before miniplates were placed in the anterior maxilla (2 just distal to the lateral incisors) and posterior mandible (2 just distal to the first molar). A cephalometric radiograph was taken after alignment and just before orthopedic traction began. Patients were instructed to wear intermaxillary elastics to the bone plates full-time beginning 20 days after plate fixation. The plates were ultimately loaded with ~450g on each side, and orthopedic traction was carried out for an average of 9 months. Another cephalometric radiograph was taken once each patient had a Class I molar and canine relationship and 1-3mm of OJ. Cephalometric superimposition of the pre-orthopedic and post-orthopedic radiographs were compared to non-treated Class II controls from another recent study matched based on age, race, observational period, gender, and skeletal maturity. Compared to controls, patients with Class II bone plates showed a significant:

WHAT THE PROFESSORS THINK

This study represents a nice initial approach to a topic for which randomized controlled data might be very difficult to obtain. The use of cephalometric radiographs following alignment and then immediately after orthopedic traction was a clever way to help account for potentially confounding tooth movement as a part of Class II correction. Using a well-matched control group of untreated Class II patients from a cohort who were apparently followed recently strengthens the data – despite the fact that 2D cephalometric analysis has limitations. It is key to note that the orthopedic effects reported (most importantly, mandibular elongation/forward-positioning) are not only larger than those described in meta-analyses with the use of more traditional appliances such as a Herbst or Twin-Block, but also that the 95%CI range is small (3.15-4.51). Of further clinical importance are the rotational mandibular changes and the overall combination of ANB and OJ reduction, with an accompanying increase in OB and uprighting of the incisors. Together, these changes suggest an absence of the dentoalveolar side-effects seen with functional appliances. What’s the bottom line for clinicians? Bone anchors, not surprisingly, show great promise for true orthopedic correction of Class II skeletal relationships, through a combination of elongation/forward-positioning of the mandible, as well as maxillary restraint. The use of skeletal plates for growth modification in Class II patients should be considered when:

Article Reviewed: Al-Dumanini et. al. A novel approach for treatment of skeletal Class II malocclusion: Miniplates-based skeletal anchorage. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 153:239-47. 2018

3 Comments

|

Curated by:

Tate H. Jackson, DDS, MS CategoriesArchives

October 2019

|

Copyright © 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed