|

On Sunday, September 30th, 2018, Dr. William R. Proffit passed away. To so many of us, Dr. Proffit was simply ‘Prof” – a lasting nickname given to him by James Ackerman when W.R. Proffit was just 26 years old. In retrospect, it was a more apt name than either Proffit or Ackerman might have guessed. Prof has been, quite literally, the single most widely influential Professor of Orthodontics in living memory. Here, the Professors remember Prof in the words of those lucky enough to have known him. Dr. David Sarver

My first meeting with the Prof was actually on my first day of residency at the University of North Carolina. He was out of the country at the time of my interview, so I did not really get to meet him until I reported for work. In my first year at UNC, my wife was working at IBM in Raleigh, and I was working one evening a week and on Saturdays in a local dental practice to make extra money. When our first semester break came, everyone left for vacation or home except me. I showed up at the department on Monday morning because my wife had to go to work. I had no money to go anywhere, so I decided I would just show up and see what was going on. As I walked past Prof’s office, he looked up from his desk and informed me that, “Dr. Sarver - school is out”. I told him my situation, and I volunteered to be of help that week, if any was needed. I can’t describe the look he gave me, but all of us who knew Prof know the look. He sighed (again, a signature Prof sigh), turned around in his chair, and on the desk behind him was a stack of manuscripts that apparently was his reading assignment from NIH for review of grants. He picked up this stack of papers, at least a foot tall, rotated back around and handed them to me saying, “Read these and summarize them for me.” Whoa, not what I expected! In any event, I retreated to the library for the next two days, read all the grant proposals, wrote up my summaries, and returned Wednesday to plop them on his desk. Thus began a long and warm relationship. The rest of the week, he had me working on all of his surgery cases and on anything else he could think of. One thing about the Prof, once he was onto something he liked, he stuck with it. The first time we went to Ono Island to work on something or another, I took him to a local seafood restaurant (a hole in the wall) on the Bay, and recommended the shrimp Po’ Boy. That is what he ordered - and a beer. Well, he liked it so much we went back the next day for lunch, and he ordered the shrimp Po’ Boy. For dinner that night? Same place and a shrimp Po’ Boy. So it went. I know that there are so many stories I could tell, and as Jim Ackerman and I were swapping stories last weekend, we talked about his intellect and how we were in awe of it. I have many personal memories of our travels together, our writing experiences together, and I summarize our working relationship as being like the proverbial carrot and stick. Prof was pretty light on the stick, but he really understood how to dangle a carrot. As soon as I was reaching the end of whatever project we were on and thought I had the carrot, he would move the carrot out a couple more feet. And so it goes… Dr. Henry Fields Bill and I were introduced at a CE course when I was a resident at UW in 1975. Two years later, we were working together and did so for over 40 years. Teaching, working on curriculum and teaching materials, research and writing Contemporary Orthodontics were all part of it. He always had a vision of what he wanted to do and how you fit in. He was a relentless worker and expected the same of colleagues. He was focused on how to make understanding of orthodontics better for students and practitioners. Better teaching methods and better research were at the heart of it. He did this as a physiologist dressed up as an orthodontist. He liked to know how things worked and he liked gadgets. Eruption--how, when, primary failure, bite force? Early treatment-- how, Cl II, III, versus what else? Equilibrium theory-- measuring it? Surgical treatment-- changes and stability? Malocclusion-- how much, where, when, who? Teaching-- was there a better way? Any physiologist would love biomechanics. His ~50 years of prominence was based, in my opinion, on his strength of organizing facts and ideas by breaking the problem down into understandable units. Simplifying and giving things structure were his forté. And, he did this with plain language. The Ackerman- Proffit diagnostic system is a good example. That, timing of treatment, and complexity, were the basis of the textbook that he wanted to be aimed at predoctoral and introductory graduate student education. He will be missed by the profession and his friends and family, and certainly by me. He had a good run, I know he was proud of it and wanted more, but he can rest and know he "did good." Dr. Brent Larson Prof was my teacher, my mentor, and my friend. It was Prof who gave me the initial opportunity to be an orthodontist, and it was he who got me my first academic position. Most recently, I had been working with him, along with Henry Fields and David Sarver, on the 6th Edition of Contemporary Orthodontics. As we worked together, I marveled at his vast knowledge and continued passion for orthodontics, and I came to appreciate Prof even more as a person. I will be forever grateful for the opportunity he gave me to know him better through this project. He continually motivated me while working on the book by saying "I've always found things get done better if you put a deadline on them," and then he would give me a deadline that I thought was not achievable - but somehow it got done. I will miss being able to speak with him on a regular basis for feedback and advice, but will continue to be motivated by the things I have learned from him over the years. Dr. Katherine Vig I first met Bill Proffit on the Raleigh Durham train station platform in July 1976. I had crossed the Atlantic from England on the QE2 with our children, aged 3 and 5, and a mound of luggage to join my husband Peter Vig, who had been recruited to the UNC Orthodontic faculty at Chapel Hill. It was a multi-carriage train from New York, and Bill Proffit took one end and Peter the other end of the train. Bill, with his knowledge of trains, knew where the luggage would be located. As I stood on this long and lonely platform, I noticed a tall man walking towards me who held out his hand and said in his slow Southern drawl “You must be Miss Kate” and I replied ‘You must be Bill Proffit’ - but how did you know it was me? He looked at me with a quizzical smile and said ‘You are the only person standing on this platform with 2 little children and a mound of luggage! Bill Proffit was a mentor, friend, and inspiration for so many of us. He defined my career in the USA with an abundance of opportunities. I was the most junior and only woman faculty in the Orthodontic department in the late 1970s – this was at a time when we had accepted our first woman Resident into the UNC Orthodontic Program. Bill Proffit’s enthusiasm and leadership defined the UNC orthodontic program. He had a brilliant, analytical mind capable of unravelling complex concepts, which made him a sought-after speaker and a unique teacher. His self-confidence was a strength in his leadership, and he was always supportive and encouraging to his Junior faculty. He was easily underestimated, with his measured speech and courteous demeanor. For those who decided to be combative, it was at their peril for Bill Proffit had a quick wit and an encyclopedic mind which made him a formidable adversary. Bill Proffit’s encouragement, support, guidance, and understanding defined my career during the 8 years I was at UNC and continued over the next 30 years. I was not alone in taking advantage of his insightful guidance, and all of us who worked with Bill Proffit knew the advantages of ‘Opportunity Time’. Bill Proffit was recognized for the speed and accuracy of his intellect and writing. His use of the English language resulted in a prolific publication record and in distilling the orthodontic curriculum for the most widely read Orthodontic textbook throughout the world Contemporary Orthodontics, currently in the 6th edition. From my perspective, it is the end of an era and throughout the world we are grieving the loss of a unique individual and leader in the Orthodontic profession. Dr. David Turpin Bill Proffit was never known to “brag” about anything he accomplished…with one exception. With every manuscript he submitted for publication to either The Angle Orthodontist or the American Journal of Orthodontics & Dentofacial Orthopedics over the period of 24 years when I served as Editor of those journals, he expressed pride in how concisely each one was written. He would claim that every manuscript he submitted was carefully crafted to be as brief as possible, without a wasted word. No puffery or extensive quotes from other authors for this department chair. To the best of my memory, he stuck to that promise throughout his highly productive career. Dr. James McNamara My association with Prof extends back over 40 years. My first lasting memory of Bill was when he invited me to speak in Myrtle Beach at the UNC Alumni meeting in 1977. After arriving in Chapel Hill, Sarah, Prof, and I drove to the beach, with my sitting in the back seat. That 4-5 hour trip was my first introduction to Prof’s humor and his style of speaking. The topics of conversation ranged from my recent to trip to visit Rolf Fränkel to his growing up in North Carolina. It was a memorable and enjoyable trip. As a side benefit, I first met one of my now best friends Rusty Long who was finishing his PhD at UNC. Many of my other close friends, including David Sarver and Jim Greer, were educated at UNC, so Prof’s influence always was present, even when he was not. Bill always was generous with his time when asked to speak at the University of Michigan. He was one of the most frequent speakers at the annual Moyers Symposium. In 1985, Prof was the first Jarabak Lecturer, speaking on the then new NiTi archwires wires. He spoke many times at the Graduate Orthodontic Residents Program (GORP) meetings. And, almost every year, he was a featured speaker at the Annual Session of the AAO. He always was willing to share his knowledge with others, both nationally and internationally. It was no surprise to me that Bill Proffit was named the recipient of the AAO’s first Lifetime Achievement Award. His grant support has been plentiful over the years. He has published a wide range of journal articles, from physiology to orthognathic surgery. His textbook, Contemporary Orthodontics, is the most widely read orthodontic textbook ever written. He also has collaborated with others in helping them write their own articles and textbooks, always giving generously of his time—even in retirement. But most of all, Prof was a mentor, to residents, dental students, and post-docs as well as junior faculty and seasoned faculty both at UNC and elsewhere. The ripple effects of his efforts have spread worldwide to affect patient care everywhere and will continue to have effects long into the future. I have great respect for the life and career of Bill Proffit. He was a caring individual who earned the respect of all around him. He always will be remembered as one of the all-time true leaders in orthodontics. Dr. Lysle Johnston Bill's death is a sad event in the history of orthodontics. He was a true giant: his book is currently the received authority on things orthodontic (especially for the ABO written exam), and his RCT was one of the first in our specialty to qualify for the secret handshake from Kevin O’Brien. Needless to say, Bill was very smart and, perhaps as a result, he was largely uninhibited by an excess of humility or collegiality (e.g., competition in the “match"). Personally, I never heard him give a bad/ill-constructed lecture; his early jokes, however, are a different matter. In truth, I rarely disagreed with him, but when I did, I knew that I had to have my ducks in a row before speaking out. It would be gilding the lily to say more. He was a true giant. Dr. Tung Nguyen I still remember excitement coursing through my veins at the prospect of meeting Dr. William R. Proffit in 2004 for my residency interview. Prof, as we affectionately call him, was a figure as large as life … a rock star, the Elvis Presley of orthodontics. The man I met was soft spoken, unassuming individual with somewhat difficult to comprehend southern accent, very different from the celebrity image my mind had created. Prof is the best teacher I’ve ever had. He has an amazing ability to distill complex concepts and information into simple organized points, “Pooh Bear” logic, as he would call it. He’s extremely intelligent, but carries himself in a humble manner. Prof not only taught me orthodontics; he taught me about professionalism, ethics, and most importantly, he taught me how to think critically. There’s something so charismatic about him that makes you want to please him or at the very least, not disappoint him. We worked harder, re-read assigned articles, and made sure our treatment plans were perfect before presenting them to him. He motivated and inspired you to be better than you thought possible of yourself. It has been a decade since I’ve completed my residency. I was in the last class to train clinically with Dr. Proffit. I feel incredibly fortunate to have had the “opportunity” to learn from this amazing man and to have been around him for most of my academic career. I will continue to learn from him, and perhaps the best gift he has given me is his passion for education and the love he has for his students, friends, and family. There are days when I tire of school politics and bureaucracy; I think about the thousands of students he has taught, motivated, and inspired, and I hope that I can have a small fraction of that impact during my career. Dr. Clarke Stevens I had no idea when I went to study orthodontics with Bill Proffit that I would find a mentor and friend. He was as interested in his student's success as his own. He challenged me in the pursuit and process of my orthodontic career. Prof helped mold a diverse dental specialty into a specialty with academic excellence and integrity. Generations of orthodontic residents must thank Prof for teaching us how to think for ourselves and develop treatment plans and orthodontic care. I thank God for giving me Prof and for Prof’s lavish sharing of his life and friends. Dr. Ching-Chang Ko, for the UNC Department of Orthodontics Dr. Proffit had a huge impact, not only on orthodontics, but also on other disciplines such as pediatric dentistry and oral maxillofacial surgery at UNC and around the world. Chapel Hill is the home of the “Proffit School”, the place where the stories shared around the globe through Contemporary Orthodontics originated. Prof will be missed by all of our departmental colleagues, students, and staff. His legacy will continue in those who learned from the master, as they pass their skills and knowledge on to the next generation of orthodontists. Dr. Tate Jackson Prof was a true friend and inspirational motivator in my life. I will miss him. Like so many of us, he gave me the opportunity to have the job - and in many ways the life - I wanted. His legacy will live in all of us whom he taught. This website is a project he supported with the energy and enthusiasm of a young man – even until the very last day he was alive. We invite you to share your memories of Prof in the Comments below.

6 Comments

The ultimate thesis of the book is that deficient jaw growth - a disease of civilization - is causing pediatric sleep apnea. The ultimate thesis of the book is that deficient jaw growth - a disease of civilization - is causing pediatric sleep apnea. BY WILLIAM R. PROFFIT, JAMES L. ACKERMAN, & TATE H. JACKSON This book is the result of an unusual interaction between a private practice orthodontist with ties to an English “orthodontic philosopher” and a prominent evolutionist / cultural anthropology professor. Its basic idea is that dental crowding and jaw relationship problems are a disease of civilization, and that the changes in behavior and jaw function produced by civilization are largely responsible for problems secondary to deficient jaw growth, with pediatric sleep apnea as the hidden epidemic. The thread running through the book is roughly:

One major problem with the theory outlined in the book: cooking, and therefore decreased stress on jaws from chewing, began well before an increase in malocclusion was seen. One major problem with the theory outlined in the book: cooking, and therefore decreased stress on jaws from chewing, began well before an increase in malocclusion was seen. Disease of civilization? Labeling malocclusion as a disease of civilization goes back to two parallel discoveries in the early 20th century: burial mounds with multiple human skeletal remains from the previous millennium, and observation of the dentofacial characteristics of previously unknown aboriginal groups who were found at the same time. It was observed that crowding of the teeth (this book’s narrow definition of malocclusion) was much less prevalent in remains from European populations from more than 400 years ago, and rare in most aboriginal populations. More recently, it was also noted that malocclusion is more prevalent in at least some large and crowded cities in India than in adjacent less-developed rural areas. Given that, is malocclusion a disease of civilization? Not a bad description, if you don’t take it too far too fast. Jaw size: function vs. heredity Some studies by physical anthropologists suggest that dental crowding is due largely to environmental, not genetic control. Even if you accept this, which is the justification in this book for assuming that stress during function determines jaw growth, there are two difficulties in extending the concept of environmental control that far. The first is that almost surely, chewing force decreased gradually over a vastly larger time scale than the more recent increase in dental crowding. An anthropological theory posed recently (and either overlooked or ignored in this book)(1) is that a key step toward civilization was learning how to produce and control fire. That allowed proto-humans to come down out of the trees, protect themselves from predators by gathering around a fire, and use it to cook food to make it more readily consumable. Data indicate evidence of cooking 200,000 years ago, and it was widely adopted by ice-age Neanderthals. The amount of stress on the jaws from chewing one’s food presumably began to decrease when cooking made food easier to chew, not when malocclusion increased just a few hundred years ago. With that difference in the time frame, can you realistically claim that a rapid decrease on stress from chewing occurred recently and that jaw size decreased rapidly because of this? Almost surely not. The second difficulty is data that refute environmental rather than genetic control of jaw growth. A major point not acknowledged in the book is that the jaws of current Europeans are quite similar in size to those of the burial mounds. Direct evidence of genetic control can be seen in the remarkable similarity of the facial proportions and jaws of identical twins, in whom minor deviations in jaw width appear in a mirror image. It also is seen in the large but internally-consistent differences between aboriginal groups. Examples are the large and protrusive mandibles of Melanesian islanders, which have not changed although their diet has; the same is true for the X-occlusion (buccal crossbite) of Australian aboriginals. In short, even if you conclude that dental crowding is largely due to environmental influences, there is good evidence of genetic influence on both jaw size and jaw relationships. In the book, pediatric sleep apnea is said to develop because the mandible doesn’t grow forward enough and doesn’t bring the tongue forward with it, so that makes the pharyngeal airway difficult to maintain. Dr. Kahn’s lengthy discussion of the path from lack of breast feeding to improper swallowing to mouth breathing to poor oral posture to sleep apnea is simply not supported by data. There are weaknesses or contradictory findings at every step, especially the part about lack of jaw growth as a cause of sleep apnea, and none of this is discussed.  100 years ago, Alfred P. Rogers presented the same theory laid out in the book. 100 years ago, Alfred P. Rogers presented the same theory laid out in the book. Orthodontic treatment by growing jaws Dr. Khan calls herself a proponent of Dr. John Mew’s approach to orthodontics, which is built around the goal of stimulating growth to correct growth distortions. A long series of studies has shown that increasing the long-term size of mandibles beyond 1-2 mm very rarely occurs even though temporary acceleration of growth was achieved. Despite that, she suggests that orthodontists who follow current treatment recommendations fail to understand that “basic evolutionary theory makes it crystal clear that claims of a dominant role of genetics can be ignored in almost all cases.” All of this is a remarkably selective resurrection of ideas that have been totally discredited. The bottom line is that Khan and Ehrlich's theory is not at all original and has been shown to be incorrect over the years. Exactly 100 years ago, Alfred P. Rogers, a graduate of the Angle school, posited the same theory as Khan and Ehrlich. Rogers was not an obscure person in American orthodontics, having served as chairman of orthodontics at Harvard and as president of the AAO. His first and most important paper, in which he coined the term myofunctional therapy to describe an elaborate set of exercises that would straighten teeth and correct jaw relationships, was published in 1918 in the International Journal of Orthodontia. He published a follow-up paper 32 years later in the American Journal of Orthodontics saying essentially the same thing but presenting no evidence that it worked, and by a few years later his methods had largely been forgotten in this country. His claims had been examined and could not be confirmed. Ballard in the UK revived a similar theory in the 1960s and promoted it with Tully’s help, but once again the claims could not be substantiated. Mews’ theories are a direct knock-off of Ballard and Tully’s work. Perhaps if you don’t know the history, you really are destined to repeat it.  Dr. Kahn distinguishes orthodontists who (in her view) only straighten teeth from dental orthopedists (also called orthotropists). This is a small group who are oriented to treat children starting at age 4 or 5 and use appliances and exercises to attempt to guide growth. She sees this, based on her own experience, as occasionally successful but potentially harmful. She now practices “forwardodontics”, a term she introduces in this book. It is based on Mew’s “orthotropics”, defined as application of the “tropic premise” that if therapy is properly directed and accompanied by stimulation of the jaw muscles, jaw growth can be stimulated. What makes it forwardodontics? It is Dr. Kahn’s conclusion that “In practically every person in modern society, both the upper jaw (maxilla) and lower jaw (mandible) are well behind their ideal forward locations for airway development,” so the major goal of treatment for everyone would be to cause both jaws to grow forward. How is this accomplished? With a combination of a removable appliance that postures the mandible forward and a series of exercises. How well does this work? Despite all the claims of effectiveness, there have been only isolated case reports of treatment outcomes for patients treated with Mew’s methods, and there is a total lack of data for results with Dr. Kahn’s suggested methodology. One aspect of cultural anthropology is the evaluation of how a group’s behavior is based on their beliefs. Perhaps that is the link between cultural anthropology and orthodontics. Dental orthopedists (and forwardodontists, if there are any others besides Dr. Kahn) treat patients based on their beliefs, not on evidence of treatment outcomes. That’s a cultural decision, certainly not a scientific one. In the real world of orthodontics and health care in general, even the best treatments work well in some patients, to some extent in others, and not at all in some. Only in a fantasy world can you promote the idea that your chosen treatment approach is the best for everyone, and that those who don’t use it should be condemned because they have refused to understand. In this book, the cultural anthropologist / evolutionist seems to have been misled by the orthodontist’s fantasy world. However it happened, the result is a deliberately misleading book that introduces an element of unwarranted fear to promote itself. The metaphor of the killer shark in the movie Jaws – an unseen and unbelieved danger until it is too late – could have been the real model for Ehrlich and Kahn as they wrote this book together. Often, collaboration of individuals from different scientific disciplines can create great synergy. In this instance, it has instead produced an exercise in mutual delusion. References: Sandra Kahn and Paul R. Ehrlich. Jaws: The Story of A Hidden Epidemic. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018 (Apr.) https://www.amazon.com/Jaws-Hidden-Epidemic-Sandra-Kahn/dp/1503604136 1. Wrangham R. Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human. New York: Basic Books, 2009.  CBCT of the same airway with the patient supine (left) and upright (right). Van Holsbeke et al 2014 CBCT of the same airway with the patient supine (left) and upright (right). Van Holsbeke et al 2014 BY TUNG T. NGUYEN Approximately 20% of adults and 2-10% of children suffer from obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). The potential impact to health includes: diabetes, stroke, heart attack, lack of concentration, fatigue, among other symptoms.(1) The financial impact of OSA is estimated at $60 billion dollars annually. These numbers alone might inspire you to embrace the growing trend of “Airway Friendly Orthodontics,” but what do those words really mean? With the potential for truly significant health impacts, it is easy to sensationalize treatment designed to improve the symptoms of OSA in children. What does current evidence suggest? In order to separate fact from fiction, when it comes to OSA in growing patients, the well-informed orthodontist must first understand three basic anatomic and physiological principles regarding airway. 1. Airway volume and cross-sectional area are influenced by head position, consciousness and inhalation/ exhalation state during image capture. The majority of CBCT studies published in orthodontic journals are captured in the upright or sitting position. Yet, airway studies have shown that minimum cross-sectional area decreases by as much as 70% from the upright to supine position.(2) In addition, airway volume and cross-sectional area decrease in unconscious breathing compared to conscious breathing. A single snapshot of the airway captured using CBCT is an anatomic image with limitations: the patient is almost never lying down or asleep. Correctly interpreting data collected in such a fashion means understanding that the true physiologic problem (OSA) might be diminished or amplified relative to the CBCT volume.  The airway changes with growth. cbctortho.com The airway changes with growth. cbctortho.com 2. Airway volume and minimum cross-sectional area both increase from birth to age 20 years, then stabilize until to the 50s, after which they slowly dcrease.(3) That means that any case report or study in growing patients needs to have untreated controls to separate treatment effect from growth alone. If appliance “X” reportedly increases the airway volume or minimum cross-sectional area in 10-12 year olds, then ideally, that statement should be made based on comparison to a control group. 3. There is often a remission of OSA from middle childhood to late adolescence. A recent longitudinal study reported only 8.7% of children diagnosed with OSA at ages 8-11 y had OSA at 16-19 years(4) They hypothesized that normal growth of the airway self-corrects the problem. This begs the question “Are we taking credit for fixing something that growth takes care of anyway?” In addition, this study found that snoring alone is not a predictor of OSA for middle-childhood patients. What is the take-home message?

References: 1. Lumeng J and Chervin R. Epidemiology of Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008; 5: 242–252. 2. Van Holsbeke CS, Verhulst SL, Vos WG, De Backer JW, Vinchurkar SC, Verdonck PR et al. Change in upper airway geometry between upright and supine position during tidal nasal breathing. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2014; 27:51–7. 3. Schendel SA, Jacobson R, Khalessi S. Airway growth and development: a computerized 3-dimensional analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012 2012-09-01;70(9):2174–83. 4. Spilsbury, J.C., Storfer-Isser, A., Rosen, C.L. et al, Remission and incidence of obstructive sleep apnea from middle childhood to late adolescence. Sleep. 2015;38:23–29.  BY WILLIAM R. PROFFIT Do orthodontists have any responsibility for advising their patients about management of unerupted third molars? In a world where new information about chronic oral inflammation and systemic health has changed views, they do. Orthodontists trained prior to the 1990s were taught that third molars with no space for eruption should routinely be removed. Ash, the most prominent professor of oral surgery at that time, said it succinctly: “To preserve the periodontal health of the adjacent second molars, third molars should be removed in young adults before root formation is complete.” In the 1990s, efforts to calculate the cost & risk vs. benefit of third molar removal came to the conclusion that for routine third molar removal, the ratio is unfavorable, and that it is better to retain the third molars if possible. The new orthodoxy became “watchful waiting” to see if an unerupted third molar caused a clinical problem before advising its removal. The risk to systemic health of chronic oral inflammation, unfortunately, was not included in those calculations because it was not appreciated at that time. In the 21st century, new bacteriologic data have documented the relationship between chronic oral inflammation and systemic health, especially to heart disease and pre-term birth. The chief of cardiology at the University of Sydney, in the most prestigious lecture at a recent Australian Orthodontic Society meeting, also said it succinctly: “I like to talk to dentists about what I do—because I need your help.” The help, of course, is in preventing and eliminating chronic oral infection, which provides access to the systemic blood flow for oral anaerobic bacteria that play an important role in the development of coronary artery disease. Because the presence of the same organisms increases the risk of pre-term birth, obstetric physicians also now emphasize the importance of periodontal health for their pregnant patients. What does that have to do with third molars? A partially exposed third molar provides a perfect site for colonization by the periodontal pathogens that produce the systemic risk. The 21st century data show, in fact, that periodontal inflammatory disease predicts periodontal pathology in non-3rd molar regions over time, and that asymptomatic patients with visible third molars have an increased risk of early periodontal disease anteriorly. Data from four major studies with a total of 8500 patients documenting the relationship of third molars to periodontal disease were summarized by White et al in Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery in 2011. If your retention patient, looks something like the image above, what do you tell the patient and parents about the third molars? You do have a responsibility to share the current information. The message needs to include the following points:

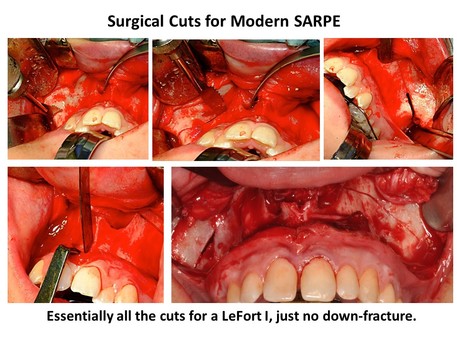

Does that mean all unerupted third molars should be extracted? No, but it does mean the third molars that carry a risk for systemic health should be extracted, and that for this type of extraction, earlier is better. Perhaps the orthodontist’s role, in addition to advising his or her own patients, also is to help family dentists understand this approach. For further information, see White RP, Proffit WR. Evaluation and management of asymptomatic third molars: lack of symptoms does not equate to lack of pathology. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 140:10-16, 2011.  BY WILLIAM R. PROFFIT SARPE (Surgically Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion) first was used with adults 30 years ago, but has undergone a major evolution since then in both indications and technique. I think it is fair to say that for many orthodontists, it is the least well understood surgical procedure for dentofacial deformity. Let’s examine four frequent misconceptions about SARPE: 1) This is significantly less surgery than a segmental LeFort I osteotomy. That was true when surgical assistance in palatal expansion for adults first appeared, because initially the surgery consisted only of cuts in the lateral walls of the maxilla. Conceptually, this was done to reduce the total resistance to expansion so that force from a jackscrew then would be able to fracture the mid-palatal suture. It is now well known that this suture becomes increasingly integrated as development proceeds, so that the force required to open it is only a few hundred grams in children below age 8 or 9 and increases to 20 kg or more by late adolescence. In young children, a palatal expansion arch (quad-helix or equivalent) creates both dental expansion and opening of the suture. For them, a jackscrew is unnecessary and contraindicated. By age 9 or 10, micro-fractures across the suture are necessary to open the suture, and it takes 1-2 kg generated by a jackscrew to fracture the interlocking bony spicules. That force increases up to around 4 kg at age 12 and then steadily to 10-20 kg at older ages. Beyond about age 15-16, very heavy force as the screw is activated results in one of three things:

For patients who need expansion, the technique for SARPE evolved to include more extensive cuts in the lateral maxillary walls extending posteriorly and anteriorly, palatal cuts parallel to the mid-palatal suture, and culminated with the addition of cuts to free the posterior maxilla from the palatine processes and other structures behind it (1). Why did that occur? Because without all the cuts to free the maxilla that are needed for a LeFort I osteotomy, uncontrolled fractures were a dangerous potential problem. In one unfortunate patient in Scandinavia, a fracture up through the nose and behind the eyes severed the optic nerves, blinding him. Less severe unanticipated fractures away from the mid-palatal suture have been noted repeatedly. The bottom line: at present, SARPE requires all of the surgery needed for total repositioning of the maxilla. The only difference in the amount of surgery between it and a segmental LeFort I for palatal expansion is the cuts to create the segments after down-fracture – as well as the down-fracture itself. 2. The jackscrew should be activated immediately and rapidly. The idea that the jackscrew for palatal expansion should be activated rapidly was incorrect from the time it was proposed because its justification was that rapid expansion would open the suture faster than bone remodeling for tooth movement could occur – and therefore it would produce more skeletal change. In fact, both rapid (1-2 mm/day) and slow (1 mm/week) expansion lead to short- and long-term tooth movement, and slow expansion results in remarkably similar outcomes to those from rapid expansion. More to the point for managing SARPE patients, clinicians now should realize that with the modern surgery, SARPE has become a classic distraction osteogenesis procedure. What does that mean? Simply that a latency period before beginning activation and an activation rate consistent with successful distraction make sense. It is true that the greater blood supply to the jaws means that the latency period can be shorter than with distraction to lengthen limbs or manage traumatic displacement, but the optimal activation rate is the same for the jaws as other skeletal areas. The current recommendations for SARPE are below: Latency period: 2 (3?) days Activation rate: 1 mm / day Activation rhythm: 0.5 mm twice a day 3. With the surgical cuts, unlike the tipping that occurs with RPE, the two halves of the maxilla move apart almost in parallel. Modern imaging techniques make it clear that this is not the case: with or without surgical assistance, the hemi-maxillae open more in the front than in the back, and rotate outward from an apex somewhere in the upper nose (2). This point leads to an important part of the surgical technique: not only are the cuts to free the posterior maxilla necessary, the cuts in the lateral maxillary walls must be widened to provide space for the hemi-maxillae to rotate outward freely. If this is not done, impingement against the zygoma may result in downward bowing of the palate and little or no skeletal expansion. For safety and for skeletal change, the modern surgical technique is a necessity. This is true for both tooth-borne and bone-borne expanders—the use of TADs does not change the need for the surgeon to freeing the maxillary attachments so the two halves can be moved without interference. 4. SARPE is needed as the first phase of surgical technique when skeletal transverse and a-p / vertical change are desired.

Why would you do that? In theory, so that in a second surgical phase the maxilla can be repositioned in one piece and the transverse expansion will be more stable. The problem with that concept is that results with one-phase segmental osteotomy for transverse changes and a-p / vertical repositioning at the same time are remarkably similar to the results with two-phase surgery. At present, there is a divide between surgeons in the northeastern US and eastern Canada, many of whom advocate two-phase treatment for three-dimensional problems, and those in the rest of the US and Canada, who usually manage problems in all three dimensions with a single surgery. The two-phase treatment has greater morbidity, cost, and difficulty in a repeat of the bone cuts that were done in the first procedure. It is hard to justify that if you can get the same results with a single surgery, and orthodontists should be sensitive to this point (3,4). The bottom line: at present, SARPE offers a slight advantage to the patient in stability and surgical morbidity when only transverse changes from maxillary surgery are needed, and a significant disadvantage when three-dimensional changes are needed. It is indicated only when transverse expansion is all the patient needs. References:

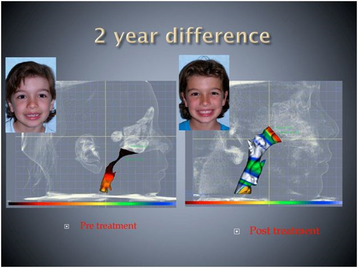

Herbst appliance Herbst appliance BY WILLIAM R. PROFFIT As orthodontics moves toward data-based rather than opinion-based treatment, clinicians may increasingly find themselves evaluating treatment outcomes in statistical terms. There are two key things that a clinician needs to know when treatment outcomes with alternative treatment approaches are presented —and often neither is presented, to the detriment of clinicians who are trying to interpret what the results mean in terms of appropriate patient care. Identifying the Level of Clinical Significance The first key item is a whether a statistically significant difference in treatment outcomes is clinically significant. Only if the difference is clinically significant should you consider a change in clinical treatment. An excellent illustration of this point comes in the evaluation of growth modification, especially with appliances that aim to increase increase jaw growth. It now is widely accepted that functional appliances can produce an acceleration of mandibular growth. Does that mean the patient ultimately will have a larger mandible? There is about a 50-50 split between the many studies of this issue that say yes or no. It helps a lot to realize that those in both camps report a possible increase of 1-2 mm in mandibular length over what it would have been without treatment. Is that statistically significant? Perhaps. Is it clinically significant? Almost surely not—if you want to correct a skeletal Class II relationship, your method had better include a decrease in maxillary growth and some compensatory tooth movement if you are only able to increase projection of the mandible by an average of 1-2mm. Improved mechanical devices are not going to change that. In the future, gene therapy or some other biologic modulation might. In the meantime, clinicians must be sure to understand the clinical significance of a mean increase of mandibular growth of 1-2mm, not just be taken by the enthusiasm of a statistically significant p-value.  Another prominent illustration of the importance of distinguishing statistical from clinical significance can be seen in the recent report in the AJODO that early (preadolescent) Class II treatment reduces the chance of injury to protruding maxillary incisors(1). That finding was reported in one of the first published clinical trials of preadolescent vs. adolescent Class II treatment(2), and a follow-up paper from the same study pointed out that the typical injury to incisors was only chipping of the incisal enamel, with obvious fracture of a crown rarely observed(3). So, the effect was statistically significant but probably not clinically significant. The recent paper, amazingly, did not consider the magnitude of injury in reporting the results—and is misleading because it didn’t. In this example, the clinician who looks to the statistical outcome alone will again overestimate the clinical importance of the result.  Cevidanes et al. Angle Orthodontist 2010 Cevidanes et al. Angle Orthodontist 2010 Understanding the Variability of the Clinical Response The second key thing clinicians need to know when evaluating statistical outcomes is important because we must be able to rationally apply statistical findings to individual patients in the clinic. Historically, the results of human subjects studies in orthodontics were almost always reported in the mean / standard deviation format. Treatment outcomes, however, usually are not normally distributed — a few patients have most of the changes— and now, non-parametric statistics not based on the normal distribution often are presented, with findings in the median / interquartile format. The size of the standard deviation, or better the interquartile distribution, tells you something about the variability in responses within a group of patients. Even with nonparametric statistics, there is a strong tendency to focus on the median and to think about the responses as being normally distributed – even when you know they were not. Is the median change is what my patient will get? The greater the variability within the group that were studied, the less likely that is to happen. It’s always true that some patients respond to any treatment better than others. Understanding the variability in patient response to a treatment is at the heart of the decision to adopt a new clinical procedure, and it is also the critical component in obtaining informed consent. To understand new data from a clinically useful perspective, the nature of the response must first be defined. Then, the individual responses—not the group response—must be examined to put the patient in the proper sub-group so that the percentage chance of favorable clinical changes can be determined. Let’s look at another growth modification example to clarify this important point. Does Class III treatment with bone anchors and Class III elastics during adolescence produce forward movement of the maxilla? On the average, the answer is yes. The mean change in the position of the maxilla is a little over 4 mm, twice the mean amount of change with facemask treatment prior to adolescence(4). But it’s more important to know that with a patient of northern European descent, like those who have been studied, you can expect 80% to have forward movement of the maxilla and one third of that group to have an increased prominence of the midface as well. 20%, however, do not have a positive maxillary response at all(5). Knowing that, would you suggest this treatment method to a maxillary-deficient adolescent? In fact, this is the most effective growth modification method that orthodontists have ever seen. What should you tell the patient and parents about this during informed consent? They need to hear about the success rate: that there’s an 80% chance of a good response and a 33% chance of an excellent response—but they also need to understand that there’s a 20% chance of no forward movement of the maxilla. Will this method decrease the chance that jaw surgery ultimately will be needed? It will take more long-term data to be sure about that, but it seems likely that it will. The Bottom Line We are in an era when orthodontists need to be critical consumers who question the information provided about advances in clinical treatment. That goes for appliances and other hardware; it also goes for treatment concepts. If the advocate of a new treatment approach cannot provide good answers when asked about 1) clinical versus statistical significance or 2) the variability of treatment success across different patients, skepticism is in order. If he or she can respond well, accepting the new information and acting on it should be the clinician’s response. References

|

Think Pieces are longer-form editorials on selected topics.

Curated by:

Tate H. Jackson, DDS, MS Archives

October 2018

Categories |

Copyright © 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed