BY WILLIAM R. PROFFIT SARPE (Surgically Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion) first was used with adults 30 years ago, but has undergone a major evolution since then in both indications and technique. I think it is fair to say that for many orthodontists, it is the least well understood surgical procedure for dentofacial deformity. Let’s examine four frequent misconceptions about SARPE: 1) This is significantly less surgery than a segmental LeFort I osteotomy. That was true when surgical assistance in palatal expansion for adults first appeared, because initially the surgery consisted only of cuts in the lateral walls of the maxilla. Conceptually, this was done to reduce the total resistance to expansion so that force from a jackscrew then would be able to fracture the mid-palatal suture. It is now well known that this suture becomes increasingly integrated as development proceeds, so that the force required to open it is only a few hundred grams in children below age 8 or 9 and increases to 20 kg or more by late adolescence. In young children, a palatal expansion arch (quad-helix or equivalent) creates both dental expansion and opening of the suture. For them, a jackscrew is unnecessary and contraindicated. By age 9 or 10, micro-fractures across the suture are necessary to open the suture, and it takes 1-2 kg generated by a jackscrew to fracture the interlocking bony spicules. That force increases up to around 4 kg at age 12 and then steadily to 10-20 kg at older ages. Beyond about age 15-16, very heavy force as the screw is activated results in one of three things:

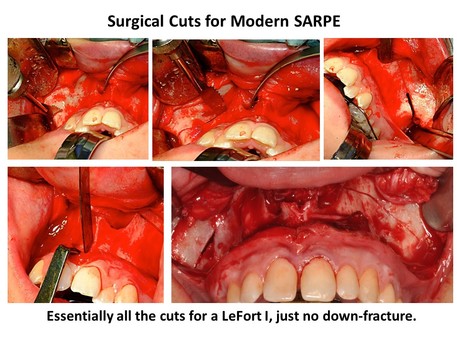

For patients who need expansion, the technique for SARPE evolved to include more extensive cuts in the lateral maxillary walls extending posteriorly and anteriorly, palatal cuts parallel to the mid-palatal suture, and culminated with the addition of cuts to free the posterior maxilla from the palatine processes and other structures behind it (1). Why did that occur? Because without all the cuts to free the maxilla that are needed for a LeFort I osteotomy, uncontrolled fractures were a dangerous potential problem. In one unfortunate patient in Scandinavia, a fracture up through the nose and behind the eyes severed the optic nerves, blinding him. Less severe unanticipated fractures away from the mid-palatal suture have been noted repeatedly. The bottom line: at present, SARPE requires all of the surgery needed for total repositioning of the maxilla. The only difference in the amount of surgery between it and a segmental LeFort I for palatal expansion is the cuts to create the segments after down-fracture – as well as the down-fracture itself. 2. The jackscrew should be activated immediately and rapidly. The idea that the jackscrew for palatal expansion should be activated rapidly was incorrect from the time it was proposed because its justification was that rapid expansion would open the suture faster than bone remodeling for tooth movement could occur – and therefore it would produce more skeletal change. In fact, both rapid (1-2 mm/day) and slow (1 mm/week) expansion lead to short- and long-term tooth movement, and slow expansion results in remarkably similar outcomes to those from rapid expansion. More to the point for managing SARPE patients, clinicians now should realize that with the modern surgery, SARPE has become a classic distraction osteogenesis procedure. What does that mean? Simply that a latency period before beginning activation and an activation rate consistent with successful distraction make sense. It is true that the greater blood supply to the jaws means that the latency period can be shorter than with distraction to lengthen limbs or manage traumatic displacement, but the optimal activation rate is the same for the jaws as other skeletal areas. The current recommendations for SARPE are below: Latency period: 2 (3?) days Activation rate: 1 mm / day Activation rhythm: 0.5 mm twice a day 3. With the surgical cuts, unlike the tipping that occurs with RPE, the two halves of the maxilla move apart almost in parallel. Modern imaging techniques make it clear that this is not the case: with or without surgical assistance, the hemi-maxillae open more in the front than in the back, and rotate outward from an apex somewhere in the upper nose (2). This point leads to an important part of the surgical technique: not only are the cuts to free the posterior maxilla necessary, the cuts in the lateral maxillary walls must be widened to provide space for the hemi-maxillae to rotate outward freely. If this is not done, impingement against the zygoma may result in downward bowing of the palate and little or no skeletal expansion. For safety and for skeletal change, the modern surgical technique is a necessity. This is true for both tooth-borne and bone-borne expanders—the use of TADs does not change the need for the surgeon to freeing the maxillary attachments so the two halves can be moved without interference. 4. SARPE is needed as the first phase of surgical technique when skeletal transverse and a-p / vertical change are desired.

Why would you do that? In theory, so that in a second surgical phase the maxilla can be repositioned in one piece and the transverse expansion will be more stable. The problem with that concept is that results with one-phase segmental osteotomy for transverse changes and a-p / vertical repositioning at the same time are remarkably similar to the results with two-phase surgery. At present, there is a divide between surgeons in the northeastern US and eastern Canada, many of whom advocate two-phase treatment for three-dimensional problems, and those in the rest of the US and Canada, who usually manage problems in all three dimensions with a single surgery. The two-phase treatment has greater morbidity, cost, and difficulty in a repeat of the bone cuts that were done in the first procedure. It is hard to justify that if you can get the same results with a single surgery, and orthodontists should be sensitive to this point (3,4). The bottom line: at present, SARPE offers a slight advantage to the patient in stability and surgical morbidity when only transverse changes from maxillary surgery are needed, and a significant disadvantage when three-dimensional changes are needed. It is indicated only when transverse expansion is all the patient needs. References:

2 Comments

|

Think Pieces are longer-form editorials on selected topics.

Curated by:

Tate H. Jackson, DDS, MS Archives

October 2018

Categories |

Copyright © 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed