The ultimate thesis of the book is that deficient jaw growth - a disease of civilization - is causing pediatric sleep apnea. The ultimate thesis of the book is that deficient jaw growth - a disease of civilization - is causing pediatric sleep apnea. BY WILLIAM R. PROFFIT, JAMES L. ACKERMAN, & TATE H. JACKSON This book is the result of an unusual interaction between a private practice orthodontist with ties to an English “orthodontic philosopher” and a prominent evolutionist / cultural anthropology professor. Its basic idea is that dental crowding and jaw relationship problems are a disease of civilization, and that the changes in behavior and jaw function produced by civilization are largely responsible for problems secondary to deficient jaw growth, with pediatric sleep apnea as the hidden epidemic. The thread running through the book is roughly:

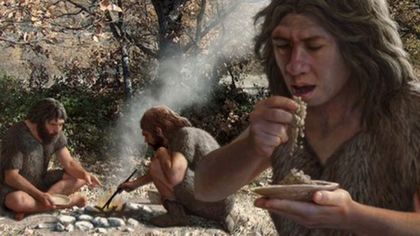

One major problem with the theory outlined in the book: cooking, and therefore decreased stress on jaws from chewing, began well before an increase in malocclusion was seen. One major problem with the theory outlined in the book: cooking, and therefore decreased stress on jaws from chewing, began well before an increase in malocclusion was seen. Disease of civilization? Labeling malocclusion as a disease of civilization goes back to two parallel discoveries in the early 20th century: burial mounds with multiple human skeletal remains from the previous millennium, and observation of the dentofacial characteristics of previously unknown aboriginal groups who were found at the same time. It was observed that crowding of the teeth (this book’s narrow definition of malocclusion) was much less prevalent in remains from European populations from more than 400 years ago, and rare in most aboriginal populations. More recently, it was also noted that malocclusion is more prevalent in at least some large and crowded cities in India than in adjacent less-developed rural areas. Given that, is malocclusion a disease of civilization? Not a bad description, if you don’t take it too far too fast. Jaw size: function vs. heredity Some studies by physical anthropologists suggest that dental crowding is due largely to environmental, not genetic control. Even if you accept this, which is the justification in this book for assuming that stress during function determines jaw growth, there are two difficulties in extending the concept of environmental control that far. The first is that almost surely, chewing force decreased gradually over a vastly larger time scale than the more recent increase in dental crowding. An anthropological theory posed recently (and either overlooked or ignored in this book)(1) is that a key step toward civilization was learning how to produce and control fire. That allowed proto-humans to come down out of the trees, protect themselves from predators by gathering around a fire, and use it to cook food to make it more readily consumable. Data indicate evidence of cooking 200,000 years ago, and it was widely adopted by ice-age Neanderthals. The amount of stress on the jaws from chewing one’s food presumably began to decrease when cooking made food easier to chew, not when malocclusion increased just a few hundred years ago. With that difference in the time frame, can you realistically claim that a rapid decrease on stress from chewing occurred recently and that jaw size decreased rapidly because of this? Almost surely not. The second difficulty is data that refute environmental rather than genetic control of jaw growth. A major point not acknowledged in the book is that the jaws of current Europeans are quite similar in size to those of the burial mounds. Direct evidence of genetic control can be seen in the remarkable similarity of the facial proportions and jaws of identical twins, in whom minor deviations in jaw width appear in a mirror image. It also is seen in the large but internally-consistent differences between aboriginal groups. Examples are the large and protrusive mandibles of Melanesian islanders, which have not changed although their diet has; the same is true for the X-occlusion (buccal crossbite) of Australian aboriginals. In short, even if you conclude that dental crowding is largely due to environmental influences, there is good evidence of genetic influence on both jaw size and jaw relationships. In the book, pediatric sleep apnea is said to develop because the mandible doesn’t grow forward enough and doesn’t bring the tongue forward with it, so that makes the pharyngeal airway difficult to maintain. Dr. Kahn’s lengthy discussion of the path from lack of breast feeding to improper swallowing to mouth breathing to poor oral posture to sleep apnea is simply not supported by data. There are weaknesses or contradictory findings at every step, especially the part about lack of jaw growth as a cause of sleep apnea, and none of this is discussed.  100 years ago, Alfred P. Rogers presented the same theory laid out in the book. 100 years ago, Alfred P. Rogers presented the same theory laid out in the book. Orthodontic treatment by growing jaws Dr. Khan calls herself a proponent of Dr. John Mew’s approach to orthodontics, which is built around the goal of stimulating growth to correct growth distortions. A long series of studies has shown that increasing the long-term size of mandibles beyond 1-2 mm very rarely occurs even though temporary acceleration of growth was achieved. Despite that, she suggests that orthodontists who follow current treatment recommendations fail to understand that “basic evolutionary theory makes it crystal clear that claims of a dominant role of genetics can be ignored in almost all cases.” All of this is a remarkably selective resurrection of ideas that have been totally discredited. The bottom line is that Khan and Ehrlich's theory is not at all original and has been shown to be incorrect over the years. Exactly 100 years ago, Alfred P. Rogers, a graduate of the Angle school, posited the same theory as Khan and Ehrlich. Rogers was not an obscure person in American orthodontics, having served as chairman of orthodontics at Harvard and as president of the AAO. His first and most important paper, in which he coined the term myofunctional therapy to describe an elaborate set of exercises that would straighten teeth and correct jaw relationships, was published in 1918 in the International Journal of Orthodontia. He published a follow-up paper 32 years later in the American Journal of Orthodontics saying essentially the same thing but presenting no evidence that it worked, and by a few years later his methods had largely been forgotten in this country. His claims had been examined and could not be confirmed. Ballard in the UK revived a similar theory in the 1960s and promoted it with Tully’s help, but once again the claims could not be substantiated. Mews’ theories are a direct knock-off of Ballard and Tully’s work. Perhaps if you don’t know the history, you really are destined to repeat it.  Dr. Kahn distinguishes orthodontists who (in her view) only straighten teeth from dental orthopedists (also called orthotropists). This is a small group who are oriented to treat children starting at age 4 or 5 and use appliances and exercises to attempt to guide growth. She sees this, based on her own experience, as occasionally successful but potentially harmful. She now practices “forwardodontics”, a term she introduces in this book. It is based on Mew’s “orthotropics”, defined as application of the “tropic premise” that if therapy is properly directed and accompanied by stimulation of the jaw muscles, jaw growth can be stimulated. What makes it forwardodontics? It is Dr. Kahn’s conclusion that “In practically every person in modern society, both the upper jaw (maxilla) and lower jaw (mandible) are well behind their ideal forward locations for airway development,” so the major goal of treatment for everyone would be to cause both jaws to grow forward. How is this accomplished? With a combination of a removable appliance that postures the mandible forward and a series of exercises. How well does this work? Despite all the claims of effectiveness, there have been only isolated case reports of treatment outcomes for patients treated with Mew’s methods, and there is a total lack of data for results with Dr. Kahn’s suggested methodology. One aspect of cultural anthropology is the evaluation of how a group’s behavior is based on their beliefs. Perhaps that is the link between cultural anthropology and orthodontics. Dental orthopedists (and forwardodontists, if there are any others besides Dr. Kahn) treat patients based on their beliefs, not on evidence of treatment outcomes. That’s a cultural decision, certainly not a scientific one. In the real world of orthodontics and health care in general, even the best treatments work well in some patients, to some extent in others, and not at all in some. Only in a fantasy world can you promote the idea that your chosen treatment approach is the best for everyone, and that those who don’t use it should be condemned because they have refused to understand. In this book, the cultural anthropologist / evolutionist seems to have been misled by the orthodontist’s fantasy world. However it happened, the result is a deliberately misleading book that introduces an element of unwarranted fear to promote itself. The metaphor of the killer shark in the movie Jaws – an unseen and unbelieved danger until it is too late – could have been the real model for Ehrlich and Kahn as they wrote this book together. Often, collaboration of individuals from different scientific disciplines can create great synergy. In this instance, it has instead produced an exercise in mutual delusion. References: Sandra Kahn and Paul R. Ehrlich. Jaws: The Story of A Hidden Epidemic. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018 (Apr.) https://www.amazon.com/Jaws-Hidden-Epidemic-Sandra-Kahn/dp/1503604136 1. Wrangham R. Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human. New York: Basic Books, 2009.

116 Comments

|

Think Pieces are longer-form editorials on selected topics.

Curated by:

Tate H. Jackson, DDS, MS Archives

October 2018

Categories |

Copyright © 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed